So I only ate potatoes for 2 weeks

2023-01-28

Last year, Jackie and I spent about 2 weeks on a potato-only diet. As a result, both of us consistently lost almost half a pound of bodyweight per day until we stopped.

Neither of us were looking to lose weight, this was just an experiment for curiosity's sake. Prior to this, I typically avoided buying or cooking potatoes because at least one observational study showed a significant correlation between potato consumption and obesity, and I don't want to be obese.

I've since gone back to a more normal diet, but I'm now incorporating more meals into my routine that consist of potatoes, because it's so unusually effective at weight management.

What is it about a potato diet that gives this unique and dramatic effect? Some theories and discussion follow.

It works because its mono, not specifically because of anything unique about potatoes

It's possible that a "only eating a single food of any kind" would be effective weight management. And there's anecdotal evidence for this online, such as with egg-only diets (and weirder stuff like pizza-only, and so on, which is obviously cheating because pizza is not a single food). There's a pretty well-known phenomenon to explain this: sensory-specific satiety (SSS). Basically, there's a "buffet" effect where a larger variety of different foods causes people to eat more in a single meal, because you can get "full" on one type of food (or more specifically, flavor), but still find room for a different food [1]. A mono diet is basically a big hack that takes this to its natural conclusion.

Mono food diets almost always seem to work initially due to the SSS hack, so it's not surprising that it works with potatoes too. But there is a pretty convincing body of evidence that something about potatoes specifically makes them more effective than any other random food, and that it isnt just SSS at work. So the fact that we ate exclusively one type of food most likely contributed to weight loss, but it's unlikely to be the whole story.

It works because of a specific micronutrient in potatoes

Potatoes are one of the highest potassium foods. At least one study has found that an intense 1 year weight loss program in obese humans with metabolic syndrome (the precursor to diabetes) found a strong correlation between the amount of weight lost and increased dietary potassium intake (study). The study also found a smaller correlation between BMI decrease and increased caproic acid intake, and decreased vitamin B6/calcium/total carbs intake. A different study found modest decreases in BMI while on an 8 week supervised diet and exercise program supplemented with a calcium-potassium salt supplement (HCA-SX), compared to a placebo (study).

To test this theory, I bought some potassium chloride and consumed it daily while on a regular diet for a week, and did not experience any weight loss, in contrast to when I was only eating potatoes. With potatoes I started losing weight after 24 hours, so I can pretty confidently rule out "potatoes work because of the potassium." It's possible that potassium chloride isn't the right formulation or I didn't take enough (it tastes terrible - like bitter and metallic table salt). The effect of potassium intake on weight loss - if it exists - is probably fairly modest on its own, and while potatoes being high in potassium maybe helps at the margin, it's almost certainly not the only mechanism.

It works because of a special protein in potatoes

Many studies involving humans and rats (study, study) seem to indicate that something in potatoes reduces appetite, stimulates satiety, and usually reduces food intake, leading to weight loss over time.

One prime suspect is a protein called potato protease inhibitor II (PPI2), which is known to stimulate release of the hormone cholecystokinin (CCK). CCK is at least partly responsible for (among other things) inducing feelings of satiety. Research into PPI2 shows promising, but not magical effects. PPI2 supplementation is definitely associated with significantly higher plasma levels of CCK afterwards, which definitely suppresses appetite and food intake in both humans and rats (study, study, study). Proteinase inhibitor even delays gastric emptying - the process of food moving out of the stomach (study), which might be part of the mechanism for how it can suppress appetite and decrease weight gain over time.

However, at least one study has found PPI2 suppresses appetite but doesn't translate to significantly different weight loss results at 20 weeks, compared to a placebo (study). The study design likely contributed to this, since both groups were given identical diets and food quantities to consume, and PPI2 doesn't change how you metabolize food, only how much you feel like eating. Meals based on potato beat out pasta and rice for satiety and fullness (study), for example, and the point is that people want to eat less food after consuming PPI2.

To be fair, other studies of potato intake or protease supplementation a few hours before a meal (study, study, study) don't show any noticeable effects on food intake compared to a control or a placebo (in some cases there was some effect on subjective hunger, but not on actual subsequent food intake). These conflicting results might be due to statistical luck, study design, or PPI2 dosage/quality issues, as the trend and mechanisms involved seem to be pretty well understood.

So PPI2 basically sounds like a magical miracle drug. The problem is that PPI2 is difficult and expensive to isolate from potato, and is challenging to manufacture and store in stable form, so the cheapest way to get the benefit is to just eat a lot of potatoes. Also, the effect is fleeting (e.g., it basically only affects the upcoming meal) so you need to be consuming it regularly to accrue its benefits over time.

It works because of the starch in the potatoes

Maybe instead of the proteins, it's the starches. My potato cooking method usually involved boiling the potatoes and then letting them cool in the fridge before reheating them. It turns out this cook-then-cool process increases the amount of resistant starch in potatoes (study), which have weird effects, one of which is changing body composition to reduce fat, but without decreasing total body weight in rats (study). A later study seems to suggest resistant starch intake (compared to placebo) reduced human appetite in a subsequent meal the same day (study).

So it seems probable that the starches in potatoes, prepared in specific ways, might increase feelings of fullness longer, separately from the presence of PPI2 stimulating the release of CCK.

It works because potatoes are not palatable

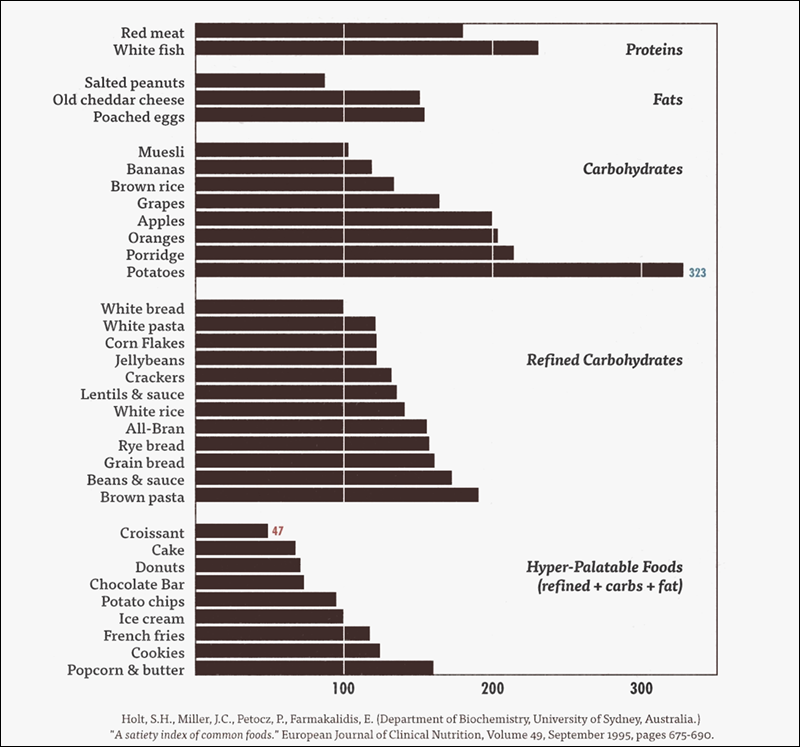

There's a famous 1995 study of the satiety index of popular foods in which boiled potatoes were found to be the most filling per calorie, by a long shot:

We've already discussed a lot of (subsequent) research on why this might be the case. But separately from that, there has been frequent speculation that the outlier potato results in this study were at least partly because of their unappetizing preparation method -- boiled, cooled overnight and then microwaved before serving - which, coincidentally, would've raised their resistant starch levels, which we already suspect increases satiety.

This might seem dumb and obvious, but the palatability of food matters! People will eat more food if its tastier! A study showed that identical cookies with alginate added took about 48% longer to chew, were rated less palatable than control, and resulted in 22% less ad-libitum energy intake (study). Feeding rats with food augmented with soluble fiber and high water binding capacity / swelling capacity reduced total food intake significantly, and tended towards a lower final weight compared to a control, although the difference did not appear statistically significant at p < .05 (study). And the Holt paper shows us that frying potatoes into potato chips makes them more than 3 times less satiating, even though it's basically the same food with different water/oil/salt ratios.

I think there's something to this. I added ketchup a few days into the diet because plain boiled potatoes were so unpalatable that it was difficult to otherwise eat enough, even when I should've been hungry given my starvation level of food intake (~500 calories worth of potatoes per day).

My related theory is that obesity rates are up because modern dieting has gotten harder -- we naturally want the tastiest foods available, and the cheapest and tastiest foods these days are cheaper and tastier than ever.

It works because of some contaminant in the food supply and I'm avoiding it by only eating potatoes

There is a popular internet conjecture that environmental contaminants are the main cause of obesity, and that lithium in particular is a prime suspect because lithium in therapeutic doses is known to cause weight gain.

The problem with this conjecture: We already know most people (with fairly limited exceptions) haven't been subjected to large and increasing doses of unintentional lithium exposure. This is pretty easy to prove! You just have to test food / random people in an obese population and find more lithium than you expect. But it turns out we basically never find anything out of the ordinary?

The more sociological objection to this conjecture is fairly straightforward. After all, if this "secret contaminants cause obesity" theory were true, there'd be career-defining incentives for someone to find it, and to date…no one has?

I just don't find this plausible in the slightest but I am listing this theory here for completeness.

Implications

I've been thinking a lot about this study since I've conducted it. The main takeaway is that plain potatoes are basically the perfect weight loss tool, and they probably contain multiple independent mechanisms that work together to control hunger and weight. The effect was dramatic enough that a brief experiment of n=2 was more than enough data to confirm the main hypothesis.

Here is a summary of our experiment rules and some answers to commonly asked questions I received:

- We bought and ate a variety of potatoes, including baby potatoes. I learned russet potatoes are my least favorite, as they are only good for french fries, and our rules explicitly banned deep frying.

- Cooking style: Usually, potatoes were boiled in the morning and eaten throughout the day and sometimes the following day. This meant that they were often cooled and then reheated by re-boiling, microwaving, or pan-frying in a small amount of canola oil. Sometimes we ate them mashed with just salt and pepper. We generally ate them without skin.

- The addition of ketchup (and pan frying in oil) was for practicality, as we otherwise found it difficult to eat enough calories and lost weight too quickly (some days we were losing almost a pound of bodyweight due to ingesting only ~500 calories).

- During this time we were doing our usual maintenance-level exercise routine of 2-3 days/week of brief moderate intensity workouts.

- We also had a cheat day every 4-5 days where we binged for 16h on things like ice cream and fried food. No weight lost on those days.

Potatoes are unusual in that they are basically the perfect mono food, with balanced quantities of macro and micro nutrients. Famously, lots of people have successfully lived healthy lives with long periods where they ate mostly or exclusively potato, including multiple cases where people voluntarily ate only potatoes for a year. The safety of this diet is difficult to dispute, and I highly recommend potatoes much more than any other mono diet that can really mess you up due to nutrient imbalances [2]. Try it today!

[1] This is apparently deliberately used in food science - many foods and recipes are engineered with a wide spectrum of flavors to delay sensory-specific-satiety for as long as possible, so that you'll eat more of it.

[2] Obviously if you have an underlying medical condition that might interact with a change in diet, you should consult an expert first and I don't take responsibility blah blah blah.

Hi Peter,

Thanks for the interesting article on a potato-only diet. Briefly, how did you prepare them? Seasonings? Condiments? Accompaniments? How many potatoes (weight or number) did you eat per day?

Thanks.

1. Mostly prepared by boiling, or boiled then lightly pan fried with a small amount of canola oil. If reheated the next day, I microwaved them straight from the fridge. I never kept cooked potatoes any longer than 48h.

2. Seasonings - salt/pepper/garlic powder, and about 2tsp of ketchup with some meals. Cooked with skin on, and mostly eaten without skin. No other accompaniments.

3. At the outset I calculated that I needed to eat about 15 potatoes per day to meet my caloric intake requirement. This is assuming around 5oz / 140 grams per potato, which is commonly described as “medium” and is roughly the size of a tennis ball or baseball. On most days however, I was only able to eat at most 5 medium potatoes. I definitely recommend you eat as much as you can, as there isn't much risk of overeating.